John Collins (1913-2001) is a guitarist known only to a small handful of jazz aficionados. Part of the reason for this lies with the fact that he was predominantly employed as a sideman, always enhancing the records of other artists, but seldom leading his own ensembles. The only recording he ever made under his own name was The Incredible John Collins (1984). By that point in his career he had already performed with such jazz royalty as Art Tatum, Roy Eldridge, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie and Milt Jackson. A consummate professional, Collins was a favoured accompanist to singers. High profile examples include Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Nancy Wilson, Carmen McCrae and Joe Williams.

John Collins (1913-2001) is a guitarist known only to a small handful of jazz aficionados. Part of the reason for this lies with the fact that he was predominantly employed as a sideman, always enhancing the records of other artists, but seldom leading his own ensembles. The only recording he ever made under his own name was The Incredible John Collins (1984). By that point in his career he had already performed with such jazz royalty as Art Tatum, Roy Eldridge, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie and Milt Jackson. A consummate professional, Collins was a favoured accompanist to singers. High profile examples include Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Nancy Wilson, Carmen McCrae and Joe Williams.

Perhaps the singer he was most often associated with was Nat King Cole. Collins joined Cole’s trio in 1951, remaining in his group until 1965. It was during that era that Cole made his much loved After Midnight album. Collins can be seen in the background of the album cover in the far right corner of the photograph. My first awareness of John Collins came from hearing his two brief eight-bar solos on the song Candy. The tune was not featured on the original LP, but reappeared on the CD reissue along with a handful of other tracks. Why Candy was originally omitted is a mystery, as the song hits an infectiously relaxed medium-tempo swing groove, and features concise turns from Collins, renowned trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison, and Cole himself. Here I’ve included transcriptions of both of Collins’ solos. They each take place during the “A” section of the tune.

With most jazz improvisations lasting for several choruses, it is sometimes useful to study miniatures such as these. Collins begins with a straightforward major-seventh arpeggio, slurring into the C natural. Note that almost every time he returns to the C note he does so with the same inflection. This helps to establish the note as a key point of interest. The triplet quavers constitute the core motif, with the opening arpeggio repeated an octave higher at beat three of the penultimate bar. Collins’ use of simple sequential repetition, clearly articulated syncopation, and question and answer phrasing, combine to produce an elegantly refined statement, the logic of which lends to it a sense of completeness. The descending triplet figure in the sixth bar of his solo utilises the Ab minor blues scale, and leads into a familiar concluding phrase.

(If any of the information on this page is of use and you would like to make a donation, please use the button below).

Collins’ second solo takes place after “Sweets” has played over the song’s bridge. He once again begins by outlining a Db major seventh arpeggio, but this time he extends it until he reaches C on the high E string. Just as he did in his first solo, Collins plays Bb-Db in quavers to usher in a timely pause. This time the pause is cut short by a legato descent into the preamble to a smoothly articulated double-time run. Throughout the solo Collins once again reveals his predilection for slurring into the leading-note of the key.

By way of a brief aside, Collins got his first break in music through his mother, the pianist and bandleader Georgia Gorham. She had him in her band for tours across the US. It was perhaps through playing with her that Collins came to the attention of Art Tatum.

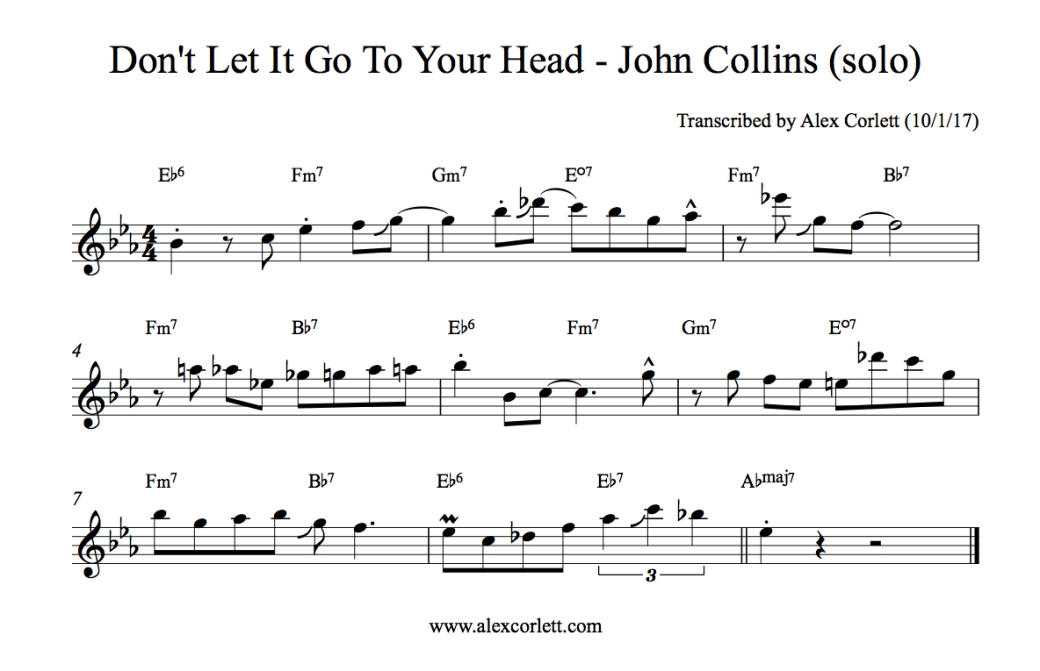

Here is another brief Collins solo from the After Midnight album. This one is from the tune Don’t Let It Go To Your Head. Just like his solo on Candy, it is elegant and concise and manages to make a strong statement in a very short space of time. Chromaticism is handled very tastefully in bar four and judicious slides help to colour certain notes.

John Collins – Don’t Let it Go To Your Head

In bar two Collins slides into a descending slur before accenting the last quaver of the bar to set up syncopation across the bar-line. The solo is relaxed and melodic throughout and features recurring motifs. For instance, look at how the second half of the first bar compares to the first half of bar five, and note the reappearance in bar seven of the slurred G to F, which first occurred on a different beat in bar three. The line in bar six makes use of a favourite device in which the interval of a major sixth is approached and followed by notes a semitone away. In this bar the Edim7 functions in the same way as C7b9.